Finding a ray of hope: FaNs for Kids' story

Dec 12, 2017

I have waited twelve years to get this information; I don’t want other mothers to suffer like me.”

- These are the words of A, a mother of two sons with intellectual disability and thalassemia living in a village in North Pakistan, where there is low literacy and no mental healthcare or caregiver services available. People have to travel miles to see a doctor, something that they can only afford to do once a year as it costs them a lot of time and money.

A is a mother of two sons aged 13 and 11. She belongs to one of the rural areas of Pakistan, Devi, a union council of Gujar Khan, where she has been settled for the last ten years. A says that women in her village do not receive any education at all.

“There are no secondary schools for girls here but I always wanted to be educated so I moved to the city of Islamabad, with my father, to continue my education.”

Fortunately, A was able to get an education until 12th grade, which was remarkable, as no one in her village had ever gotten this far in education – be it male or female.

However, as soon as she completed her 12th grade, her father married her to one of his acquaintances who was a farmer in his village. “I had to come back to my village and live here, which was a challenge for me.” Little did she know that this was not her biggest challenge; she became a mother to two sons with intellectual disability, along with thalassemia, who looked and behaved differently from other children. This had been a grief-stricken experience for A.

“I have been struggling with them for as long as I can remember.” There are very few child psychiatrists in these rural areas and the waitlist is as long as 13 months.

That is not the only problem A has to face – she has to battle the stigma that surrounds her and her children. She has to bear the critique and answer questions of her family, extended family and neighbours, as they do not understand her children’s condition; they often ask, “why do they look like that” and “why are they not able to talk like other children?” Did she commit a sin and is now facing the consequences? Even her husband does not understand his son’s physical and facial features; he often questions if this was because of her? A would avoid going to family gatherings, as she knows she would not be accepted there anymore.

***

‘Developmental Disorders’ is an umbrella term which includes intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Children with intellectual disabilities appear to have slow growth; they start to sit, walk and talk later than other children, experience functional problems as they grow (such as being unable to perform ordinary self-care), and have trouble dressing and/or feeding themselves. Moreover, they have poor development or understanding of social skills, and are unable to follow social rules and customs (such as taking turns or waiting in line).

These conditions are more prevalent in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to higher-income countries (HICs). Studies have shown that about 75% to 85% of individuals with mental health disorders in low-income countries do not have access to health care services, which increases the burden on families and deprive children from having a high quality of life.

In Pakistan, 12.6 million children are living with developmental disorders; and 100% of these children don’t receive the care they need. There are a number of factors that cause the care gap:

- Socio-political issues and conflict in some areas have pushed Pakistan to the brink of a fragile state, and have limited primary health care initiatives.

- Public spending on health is low; in 2009, health care spending amounted to just over 1% of gross domestic product, of which 5% was allocated to mental health.

- Specialist services are rare, concentrated in urban areas, and inaccessible to most.

These factors are compounded with poor awareness of the condition in family members and front-line health providers, which leads to delay in recognition and appropriate management. There is also considerable stigma and discrimination affecting such children and their families.

A got to know about the FaNs (Family Networks) 4 Kids program through an IVR poster and desperate to get any help for her children, she immediately enrolled as a Champion Family Volunteer.

One day after coming back from the farm, A encountered a female health worker who was distributing a leaflet which included information on key signs of a developmental disorder, a motivational message, and a free phone number. With doubts and many questions in her mind, A dialed the given number and a pre-recorded voice appeared asking 10 simple questions related to child disability. A, with a trembling heart, answered all 10 questions. At the end of the questions, A was asked to leave her address and contact number, and was asked if she was willing to be contacted.

What it means to be a Champion volunteer?

A was now a part of the volunteer family network – an active, empowered group within the community. A, by using a “task-shifting approach”, was trained and supervised by specialists to not only provide evidence-based interventions to her own children but to cascade it down to other families in her village as well. The network supported each other, and would train new family members who joined the group. The group worked together, village by village, to reduce the stigma associated with the condition and improve opportunities for participation in community life.

How does it work?

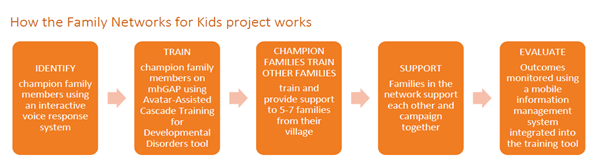

Through an interactive voice response (IVR) system, a champion family volunteer is identified. After recruiting the volunteer, they are trained through an Avatar-Assisted Cascade Training (ACT) system that contains interactive modules with story-telling avatars. The training scenarios include “real-life” narratives of the lives of three children with developmental disorders, “Bano,” “Babloo,” and “Beena,” their family members, and other supporting characters. These training scenarios can easily be updated, modified, or added to without disturbing the overall architecture of the software.

Pilot

The pilot project was delivered by the Human Development Research Foundation (HDRF), The University of Liverpool, and Institute of Psychiatry – Rawalpindi, and was funded by Grand Challenges Canada (GCC). The pilot project was successful in:

- Establishing 1 self-sustaining Family Network in a rural population of around 30,000

- Developing mobile-tech assisted programmes for their training and supervision

- Training 10 champion family volunteers, supervised by HDRF

- Providing care to 70 families of children with developmental disorders

- Creating a network that campaigned for better facilities for the children in local schools and primary health care centres, and pushed to improve participation in community life

- Evaluating the impact on children with developmental disorders and their families

How does it affect A?

A never knew children could be engaged through play activities “It took a while but gradually my husband and I started noticing changes in our children’s behaviour. The happiest day for me was when they started learning the alphabet; this gave me a ray of hope. I am very hopeful that my children will keep improving.” A wants to be a supporter and spread this ray of hope to other parents and children in her area with similar conditions through peer training sessions.

A did not only get trained and help her children in this program, but she was one of the active champion volunteers of the self-sustaining Family Network who successfully delivered the program to 5 to 7 families from her village, and campaigned for better facilities for the children in local schools and primary health care centres.

“The encouragement from my trainer and support group has given me the confidence to spread this ray of hope to other parents in my area going through the similar difficulty. It felt great when I started giving training sessions to mothers in situations like me. I travelled as far as two kilometres away on foot to give these training sessions. I want mothers to learn these skills and apply them to their children for more effective outcomes. Due to lack of education and awareness, it wasn’t easy to engage mothers and families of children with development delays. Initially, they did not show much interest but once they saw improvements in their children, they wanted to know more. It was very rewarding to see mothers working with their children towards a better life”.

FaNs for Kids is one of the innovations working with Ember. In September, this story was presented at the Time to Act Event at the United Nations General Assembly, in New York. In addition, last week, on World Mental Health Day, FaNs for Kids was represented at the inaugural Global Mental Health Summit in London by the Ember team, and colleagues at Mental Health Innovation Network.