Sustainability, Impact and Wellbeing in Global Mental Health: A community-based perspective

Nov 28, 2023

Ensuring the sustainability of an organisation, measuring the impact of interventions, and safeguarding the wellbeing of teams are usually topmost concerns for most nonprofits.

How do community-based mental health initiatives (CBMHIs), often working in low-resource settings, see these challenges? And how is their approach to sustainability, impact and wellbeing unique?

In September 2023, Ember's parent organisation, the SHM Foundation, Segal Family Foundation, and Fondation d'Harcourt organised the Sparks Meet-Up, an event in Nairobi, Kenya, bringing together diverse stakeholders in Global Mental Health to share knowledge on how to tackle these very challenges.

To find out what mental health practitioners working on the ground have to say about these three issues, read below.

Thank you to the brilliant illustrator, Mijide K., for capturing these perspectives so brilliantly. You can check out her work on social media here and here!

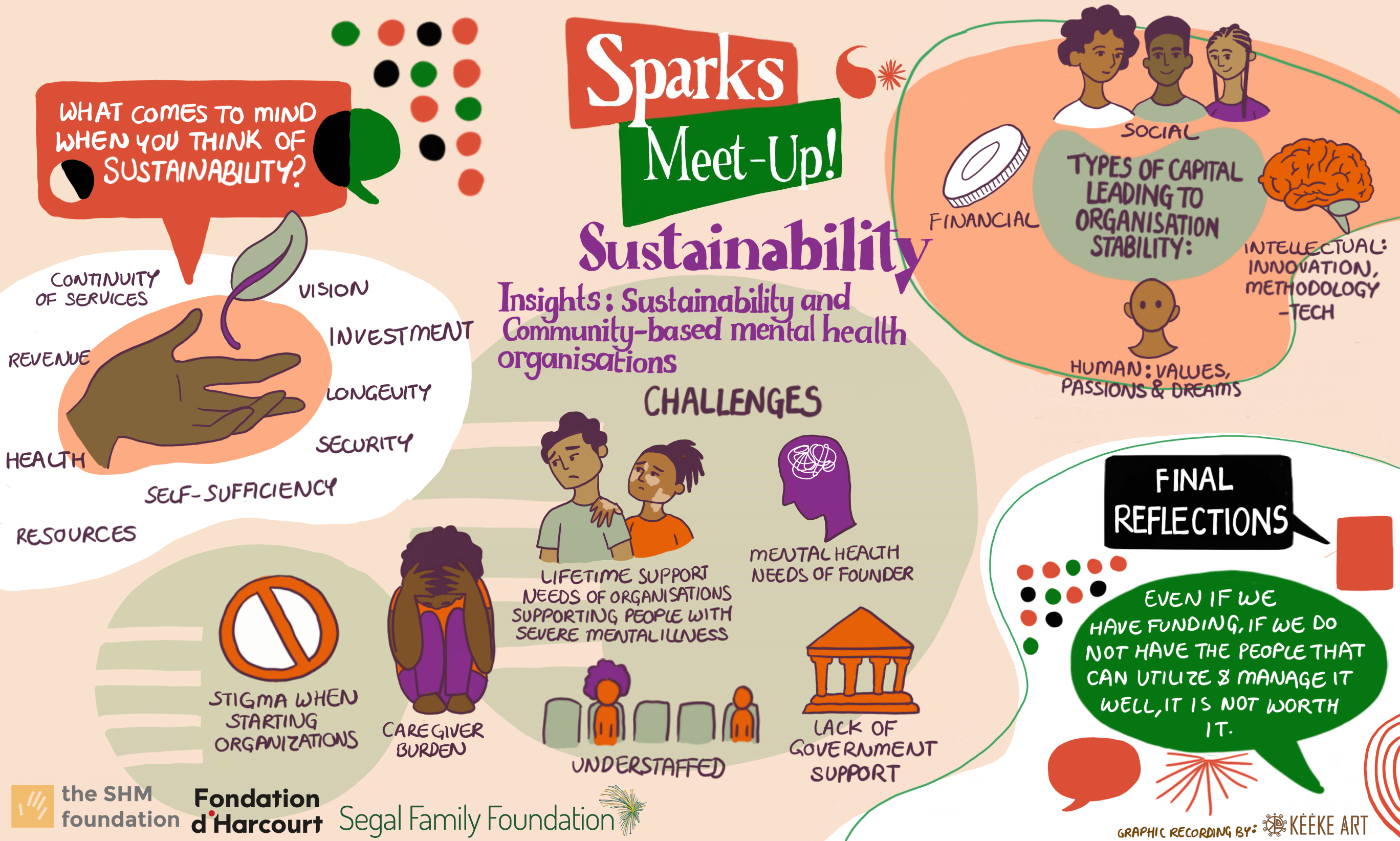

Sustainability

CBMHIs face unique challenges that require unique solutions. This is particularly true when it comes to sustainability: long-lasting funding models, scale and replication look completely different for grassroots organisations.

At the dynamic conversation on community-based sustainability at Sparks Meet-Up 2023, panellists unpacked what makes these challenges and solutions unique.

The panel was introduced by Urszula Swierczynska, Philanthropy & Impact Investing Advisor for Fondation d’Harcourt and Rini Sinha, Head of Strategy & Creative at the SHM Foundation, who discussed the dependence of CBMHIs on four types of capital – financial, human, intellectual and social. This means that organisations depend not only on investment for sustainability, but on knowledge, values, innovation, technologies, relationships, and ways of working.

As Birara Lorette and Niyokindi Christine from AVSI told us, local partnerships are 'synonymous with sustainability.' Strong ties with local volunteers are the key to sustaining community-based initiatives, filling the gap between state aid and community.

Dr. Timothy Adebowale from Hope Restoration and Health Initiative spoke on sustainability for organisations working with people with severe mental illnesses and related challenges.

Ephrata G Worku, from the Mental Health Service Users Association (MHSUA) discussed the challenges organisations led and run by people with lived experience face when striving for sustainability. She spoke of the stigma barriers that detriment these organisations from the get go – of needing a note from a therapist, for example, proving one's 'mental stability' before being able to start an organisation. For small organisations, meeting donor requirements is often a hurdle for sustainability, too.

Michael Migayo Njenga, Regional Mental Health Advisor at CBM Global Disability Inclusion Kenya discussed best practices on funding and sustainability based on CBM’s recently released guide for local partners. Michael demonstrated the importance of the state's protection and respect for CBMHIs, arguing that cooperation with the state is part and parcel of sustainability. He argued further that mental health laws and practices must be accountable to local communities. For organisations providing solutions to local problems to be sustainable, there must be a transfer of power and resources to empower people at grassroots to be responsive to local priorities.

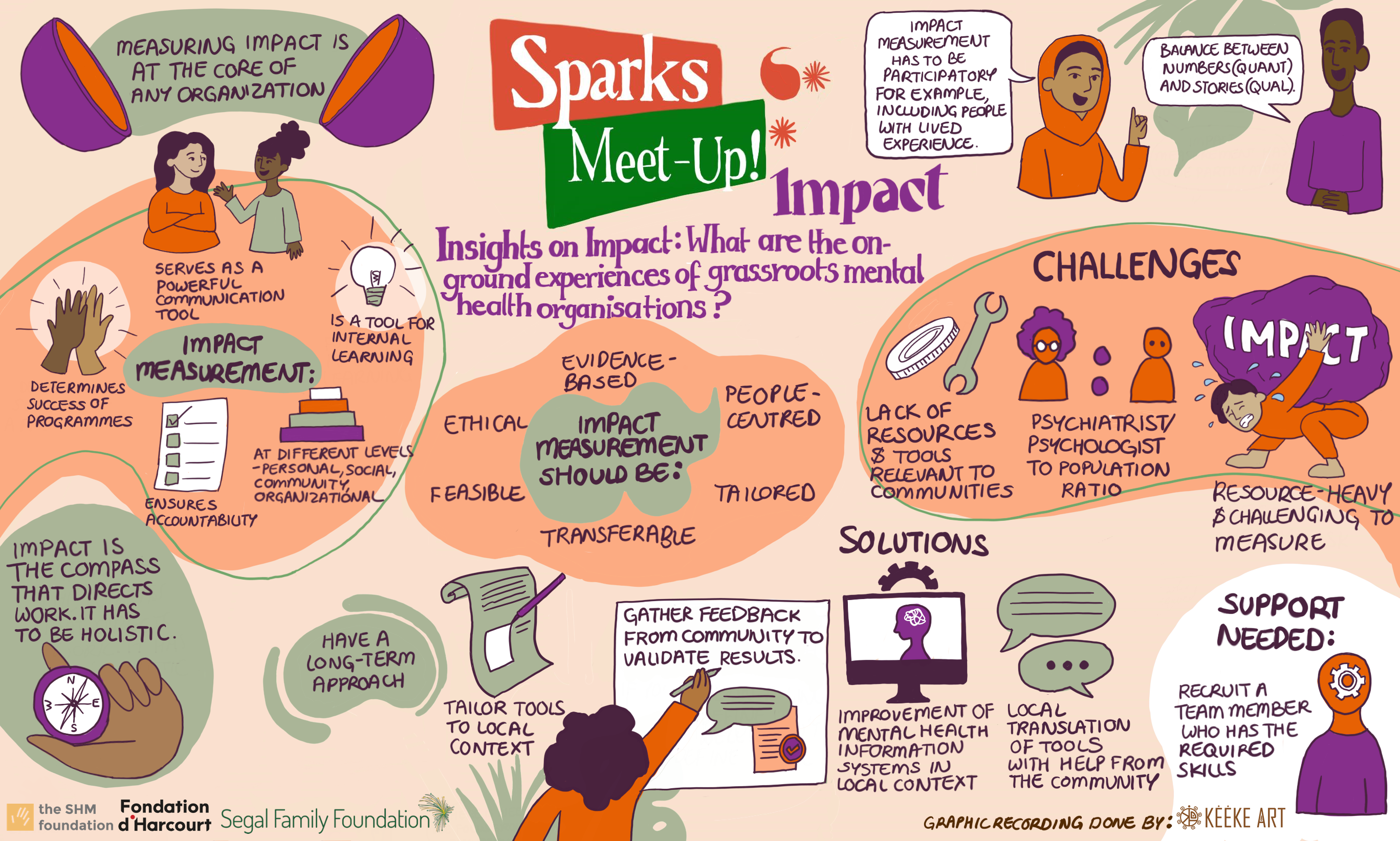

Impact

Impact, as SHM Foundation's Impact Team, June Larrieta and Georgina Miguel Esponda, put it, is 'a mirror we hold up to ourselves'. Or, as Bright Shitemi, founder of Mental 360 put it, it is 'the compass that directs our work.' Impact measurement allows organisations to understand the success of their programmes, serve as a tool for internal learning as well as a means of communicaton. It helps us to keep promises and focus on our goals.

For community-based initiatives, impact measurement can be seen as rigid and unnatural – quantifying wellbeing through a generic questionnaire often feels like a reductive and unrealisic way to do things. Resource strain, time, tech skills and capacities limit impact work for many CBMHIs, too. Georgina and June showed how, at Ember, we are working on diverse, flexible impact research that fits the needs and capacities of grassroots initiatives.

We heard from Bright Shitemi, founder of Mental 360, about the need of impact activities to be in touch with the communities served by initiatives; or, in their words, 'not designed in a lab.' Every tool must be context specific.

But how exactly can impact measurement be made relevant to communities? Florence Adong from PCCO, Uganda, stressed the importance of participatory approaches to collecting impact data, such as focus groups. What's more, it's imperative that the findings of these investigations are shared with the community that implements and benefits from the intervention. Florence echoed Bright's earlier reflections on the need to share success stories with a wider audience – avoiding generalisations but ensuring that the real changes made in communities are reflected.

When asked about their impact measurement tools, representatives of CBMHIs listed a variety of tailored approaches, from digital workbooks that produce qualitative data to quantitative evaluation carried out psychologists. Florence emphasised the need to ask participants how they would like the impact of their work to be measured and represented as a first port of call.

Vongai from Positive Konnections, an Ember investee, illuminated the impact measuring challenges of her organisation: as the one psychologist working for 1 million people in Zimbabwe, Vongai's priority until 2022 was providing essential services with limited resources, meaning impact measurement had taken a back seat. As Claudia Sartor from GMHPN pointed out, impact measurement often requires the appointment of a new staff member with the necessary skills – which requires more resources. For CBMHIs struggling to cover core costs, this is not always possible.

Claudia, among others, stated that various changes must be made in impact measurement to suit the needs of CBMHIs: the inclusion of people with lived experience of mental health challenges, the improvement of mental health information technology, and an acceptance by funders and initiatives alike that impact measurement takes time, dedication and resources.

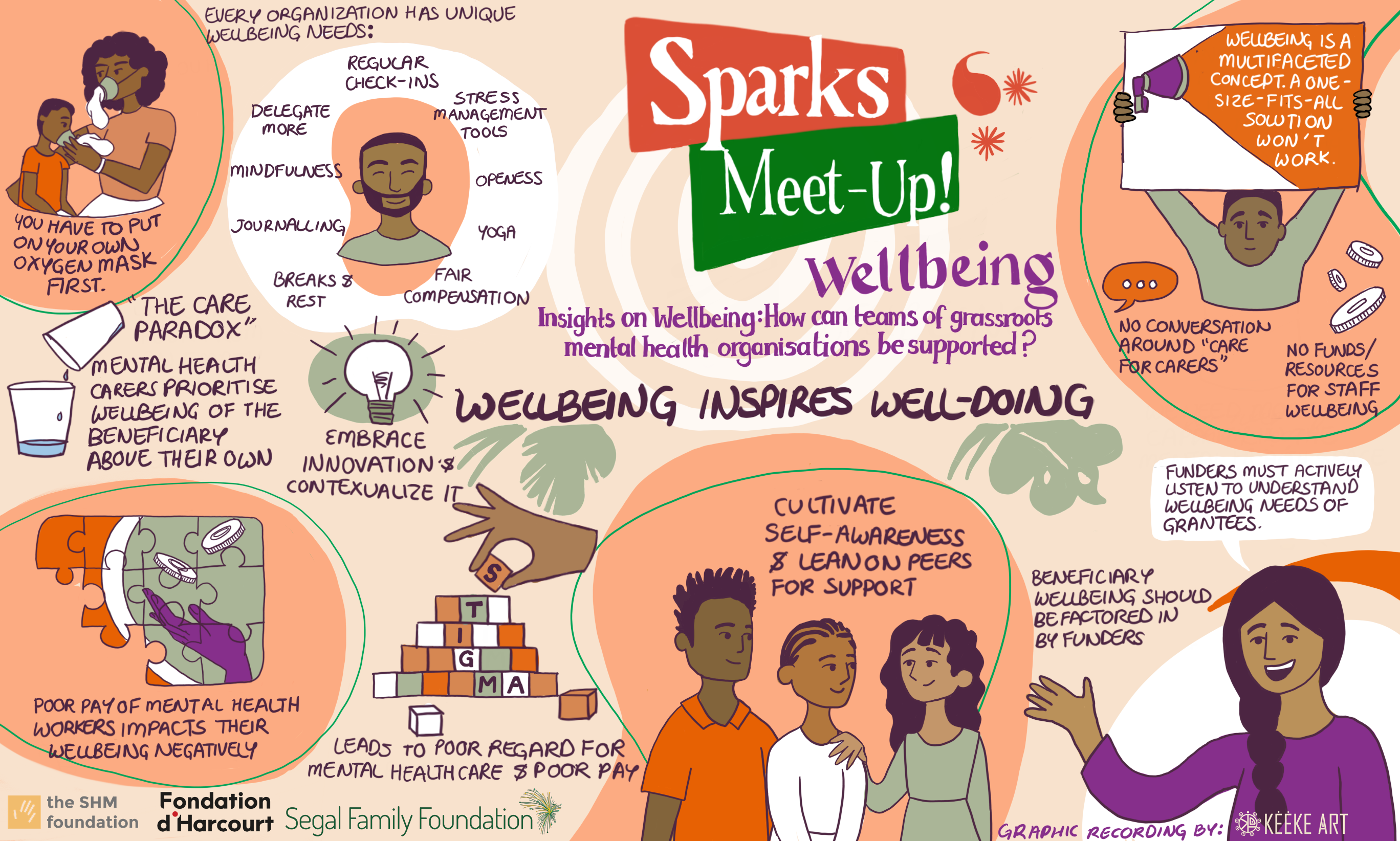

Wellbeing

Carers deserve a high standard of wellbeing just like anyone else.

Too often, however, mental health carers prioritise the wellbeing of their beneficiaries above their own. But, as the saying goes, you can't pour from an empty cup.

Rosemary Gathara, Executive Director of Basic Needs Basic Rights Kenya, discussed the structural barriers to looking after the wellbeing of mental health carers in community-based organisations. The pressure on grassroots organisations to stand in for states that do not adequately care for the mental health of their citizens has a profound impact on staff members.

This pressure, paired with the constant exposure to the difficulty of others, means that carers urgently depend on stable funding allocated to support their wellbeing. As Geoffrey Khira from the Kenyan youth organisation Mental Health and Wellbeing on Campus states, 'Burn out is real. Second hand trauma is real. Fatigue is real.'

However, in most cases, this is far from the reality. Fluctuating finances result in short-term contracts for employees, and a systemic lack of core cost funding means that grassroots organisations often cannot afford to look after the wellbeign of their team.

So, how can the wellbeing of mental health workers in grassroots intiatives be supported?

Staff at Girls for Girls Africa Mental Health Foundation (G4G) provide mental health, educational and legal support to people affected by sexual and gender-based violence. This sensitive and difficult work means that, without proper measures, carers can become overwhelmed. When asked how the wellbeing of her team is protected, Queentah Wambulwa, founder of G4G, stressed the importance of both short-term and long-term measures.

On a daily basis, Queentah ensures that no staff member leaves without a debrief to 'get back to their normal self'. Every day, each staff member is asked, on a scale of 1-10, how they are mentally feeling.

Many grassroots mental health initiatives have proactive approaches to wellbeing like this. Some suggested a scheme where, on a weekly basis, staff come together for a two-hour, technology-free check-in session. Others shared that their staff are able to take wellbeing days as and when needed. A suggestion that particularly resonated with the audience was one day a month where office attendance is required, but work is not. This means coworkers can get to know one another and form bonds outside of the difficult jobs they do.

Aside from practical measures like this, Queentah emphasised that it is important to foster a culture of wellbeing on the whole. Flexible and forgiving working conditions must come alongside a culture of oppenness, acknowledging second-hand trauma, and ensuring that staff feel motivated and rewarded for their work. On paper, this looks like having funds allocated for wellbeing and decent salaries for staff.

Wellbeing entails the physical, emotional, spiritual, financial, nutritional, social and intellectual welfare of individuals and their communities. A culture of wellbeing in grassroots organisations must incorporate these multiple intersecting factors – no small task, but one that is receiving growing attention, respect and resources.